"It's so commercial now!"

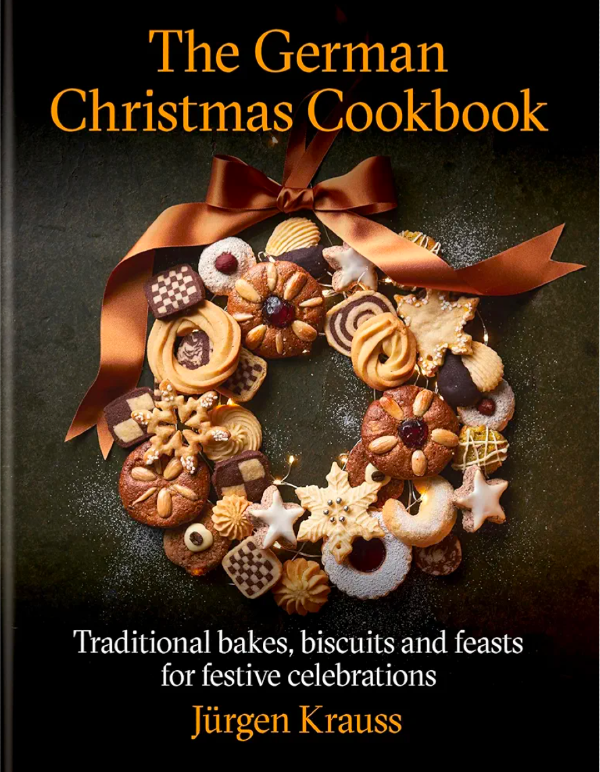

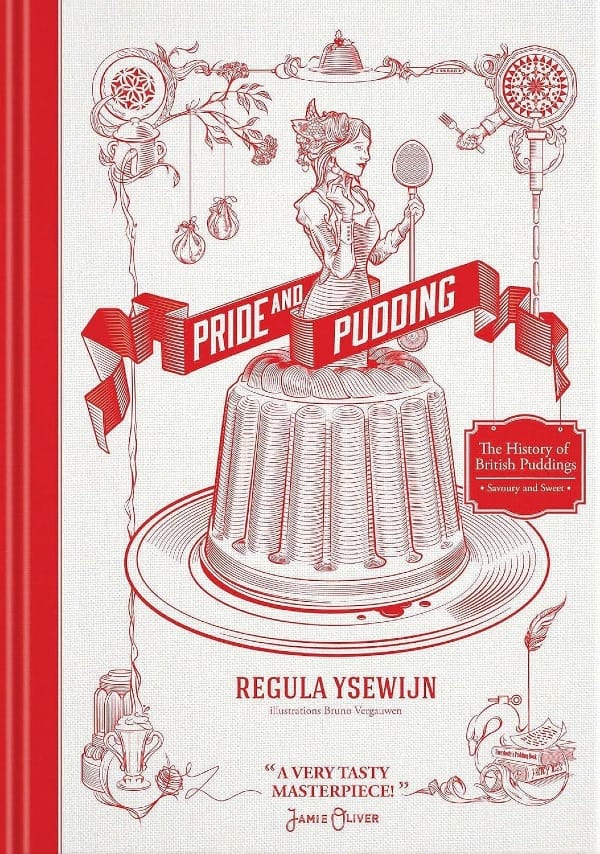

My personal take on Halloween and Día de Muertos, a prequel to a post about Halloween-themed cookbooks and food writing. I'd love you to subscribe to my newsletter; there's a link on the homepage.

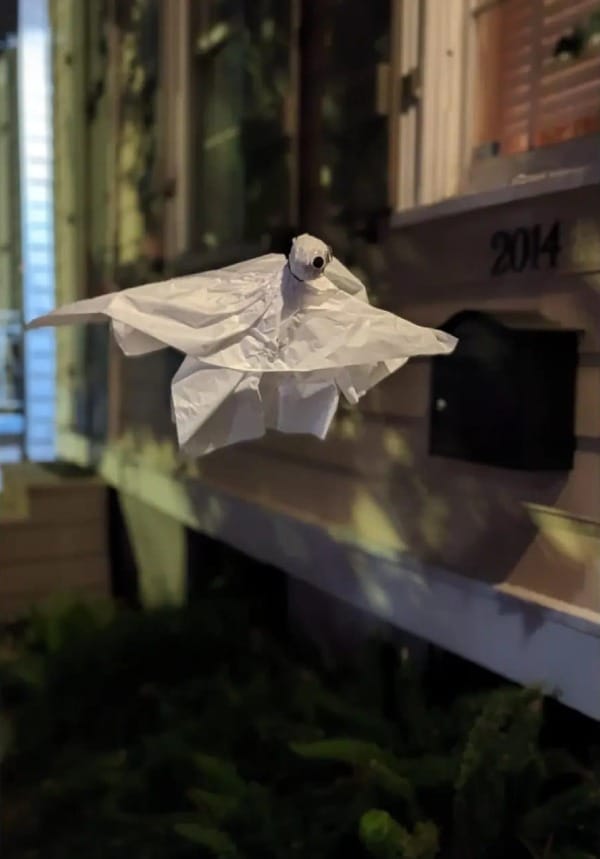

Halloween was a slightly ramshackle affair in late seventies-eighties England. Back then, airing cupboards were raided for white sheets to be thrown over heads. We'd use a red felt-tip pen to draw on bloodstains, and carry plastic bags for our loot. Trick-or-treating was pretty basic, but it happened. Fruit Salad and Black Jack chews, packets of Spangles, tangerines (you have to remember that these were a real treat in the seventies, just 20 years or so after the end of rationing), apples hastily grabbed from fruit bowls by neighbours caught on the hop and flying saucers in pastel rice paper that became a soggy mush after being carted around for three hours were some of the spoils. We made do and didn't have a problem with this. Back then, there were almost no Halloween-themed products in shops, except for the odd witches' hat and broom, and very little decoration; the whole event took a back seat to the far more exciting Guy Fawkes Night the following week.

Things have changed. Brexit and the post-pandemic economic downturn pushed many businesses into survival mode. They have to find ways to rebrand existing products and services for Halloween to attract customers who might have less money in their pockets but still seek opportunities to add colour, joy and novelty to their lives without breaking the bank. Some of our biggest public Guy Fawkes firework displays have been cancelled in recent years, and domestic fireworks are increasingly discouraged, leaving Halloween to fill the gap. I went for a walk this morning around my neighbourhood and noticed that the first decorations have gone up. They're noticeably more creative. Windows have been shrouded in black lace and net, and huge spiders, skeletons and ghouls hang from the guttering. There are a lot of pumpkins.

When the nights are long and the days increasingly grey, the vibrant imagery of North American Halloween and Día de Los Muertos celebrations is extremely seductive for us northern hemisphere folk. I am a summer baby (a double Leo!) who dreads winter, but my social media feeds are a joyous riot of colour and life right now. My Mexican friends are posting reels of their costume-making process in preparation for Día de Muertos, and soon Instagram will be filled with photos of sugar-encrusted, brightly decorated pan de muerto. Oktoberfest's platters of sausages, bronzed and tawny pretzels and rich dark beer are beginning to appear, as will Diwali's trays of mithai, fireworks, and diyas, and the Chinese Moon Festival's glowing red lanterns and mooncakes. Our soups are changing colour from summery verdant greens and acid-reds to shades of feuille-morte and golden-brown harvests, and the pick-your-own pumpkin patches are about to throw open their gates.

Pumpkin patches are a well-established autumn tradition in the USA and Canada. The fact that they are extremely Instagrammable drives their popularity, and UK farmers have recognised their potential for increased revenue at a relatively fallow time of year. It's hard to pinpoint an exact date when the first UK pumpkin patch opened, but Crockford Bridge Farm in Surrey welcomed the public in the early 1990s after years of growing pumpkins as part of its crop rotation practices. Since then, UK farmers have diversified further, taking their lead from North America, adding pop-up food concessions, coffee trucks and bars, employing designers to stage picturesque photo opportunities, and running special evening events including carving sessions, pumpkin cooking classes, and even providing recipe cards for visitors to take home.

Here in East Anglia, the fields are dotted with vibrantly orange Jack 'O Lanterns and their smaller brother, Jack Be Little, which, when unsold, are left to collapse in on themselves like deflating hot air balloons to be ploughed into the soil the following spring. Their skins glow in the autumn light; they are unmistakable and (to me) a little exotic. I resisted their lure for a long time until a visit to a local patch saw me return home three hours later with at least twelve different squashes; some to eat, the rest for decoration (although the ones left outside for several months still made good eating). I felt like I was in a real-life Hallmark movie. I'm still not used to seeing pumpkin patches in the UK; they feel incredibly North American.

The best patches offer a mix of heritage and hybrid varieties of squash and gourds. I love to read their names out loud:

Bambino, Big Max and Miss Sophie Pink (who sounds like an Edwardian heroine). The delicious Crown Prince. Jumbo Pink Banana and Volskaya Grey, Blue Kuri and Uchiki Kuri. Garbo (although squashes, being field crops, really do not like to be alone!). The fugly Galeuse D’Eysines, whose warts are actually sugar blisters that rise as it ripens. Black Kat, Warts Galore and American Wings, the goths of the squash world. Cute little Casperito (a farmer told me children love these little white squashes) and the equally cute Bush Baby and Honey Bear. And the elegantly named Italian Lunga di Napoli and Piachenza Beret (aka medieval hat squash).....In the USA, you can even buy teal pumpkins to let trick-or-treaters know your household is food-allergen-aware. A local grower told me kids adore white pumpkins, something a British chain store has capitalised on, labelling them 'Ghost Pumpkins'.

Speaking personally, pumpkins have always been synonymous with autumn (or 'Fall') in North America. I blame this in part on my total adoration of all things Peanuts and the 1966 TV special 'It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown' in particular, which I watched as a child in northern Mexico, where exposure to US popular culture was inevitable. A short précis: Linus accompanies his sister Lucy to the pumpkin patch to select a pumpkin to carve ("You didn't tell me you were going to kill it!" he says when she starts hacking away). Clutching his security blanket, he returns to the patch at night to await the arrival of The Great Pumpkin, whilst the others prepare to go trick-or-treating. They laugh at him, and mock his faith, and when, finally, a figure (Snoopy, not The Great Pumpkin) rises from the patch, Linus faints. His sister eventually drags him home. Described by writer Rich Cohen as "the purest parable of faith I know" and condemned by others as blasphemous or—at the very least— pagan, I could not love a cartoon more.

This was possibly my first exposure to a Jack 'O Lantern, although the custom is not native to modern-day USA, and people with Latin American heritage do use pumpkins in deeply symbolic rituals and traditions. Ancient Britons used to carve turnips during the Celtic holiday of Samhain to remind themselves of 'Stingy Jack', who was made to wander the earth carrying a turnip lantern lit by a single burning ember after tricking the Devil over payment for a pint of beer. It was believed the veil between the world of the living and the dead grew thinner at Samhain, making it easier for their spirits to return, so lanterns were placed on windowsills to ward off Jack (and evil spirits). This tradition crossed the Atlantic as Irish immigrants flocked to the USA for a new and better life. Eventually, pumpkins, being indigenous to the Americas, replaced turnips. In Mexico, they are everywhere.

I celebrated Día de Muertos in Mexico, where I lived as a kid. Its ceremonies reflect the Pre-Hispanic belief that all life is engaged in a perpetual process of destruction and creation. Mexicans believe this to be a time when it is easier for the living to communicate with the dead; altars are built to honour dead loved ones. They welcome the return of the spirits of those who died from suicide, stillborn babies and tiny children who died young (Día de Angelitos); those who had no relatives to mourn them; and people who died violently or nobly. Shrines appeared at my school and the homes of neighbours. It was important to visit and show respect. An offrenda would be made to the spirits: “Pues el difunto podria volver ese día a la casa y hay que atenderlo bien.” (You see, the deceased might return home that day, so one has to look after them well). A wash basin, mirror and grooming products were placed on one tier of the altar so spirits could cleanse themselves after their long, tiring journey from Mictlan (the Aztec Underworld) before joining the festivities. My friend buys a new tub of Tres Flores pomade for his altar because his long-dead father would come home with 'wild hair' after a day's work. Another friend treats his mother to the expensive Chanel perfume she coveted but would not allow him to buy for her in life. He cannot bear to throw away the hair trapped in his mother's hairbrush but knows she would be furious with him for placing it, uncleaned, on the altar. So he removes the strands, then washes and replaces them after the altar is taken down.

Noon bells tolled on November 2nd as the spirit elders (The Faithful Dead) arrived home before we paraded to the local cemetery at dusk, accompanied by mariachis. The ceremonial meal started with clay jugs of corn-based hot chocolate. We ate pork and squash-stuffed tamales, skull-shaped pan de muerto (anima) and candies (calaveras) made from sweetened, milk-enriched pumpkin flesh. Although we lived in the North, many of our friends had ancestral ties to southern Mexico, having migrated north to work in the city's flourishing automobile industry. Their customs came with them. So some families might remove the dead from their tombs, wash and wrap their bodies in clean shrouds scattered with marigold (cempasuchil) petals, helped by neighbours in a celebration of grief, love and family. Others would clean their family tomb, inside and out, but leave the bodies of their loved ones inside. We children danced, played games, cadged candy from the grownups, then fell asleep against the tombs, wrapped in blankets to keep us warm in the desert night. I remember so much: the spicy smell of marigold flowers trodden underfoot, the bruise-purple mountains encircling our neighbourhood on the edge of the city, the scent of hot, scorched corn, the reminiscing, the sheer vivacity of life.

The relatively recent adoption of Día de Muertos celebrations in the USA, as part of the Chicano Movement to encourage cultural pride in the Latin diaspora, resulted in the political slogan “Día de los Muertos is not Mexican Halloween” in response to non-Latinos confusing the two. In an article for The Conversation, Dr Mathew Sandoval, a cultural historian and performance studies scholar, describes the line drawn between the two festivals as a "rhetorical strategy to protect Day of the Dead’s integrity as Mexican cultural heritage and separate it from American popular culture", whilst acknowledging the cultural intermingling we see today. The United Nations classified Día de Muertos as an intangible cultural heritage in an attempt to protect the festival from cultural dilution, but "it was too late", according to Sandoval.

"The useful question isn’t whether Mexico “does” Halloween. It does—loudly in cities and border towns, softly or not at all in some rural communities. The better question is how Halloween slots into the national choreography around Nov. 1–2, Mexico’s traditional holiday of Dia de Muertos", writes Letitia Bravo for The Mexico Edit. She describes Halloween as "the public-facing pregame to Día de Muertos, and its influence runs through the surface—shop windows, school corridors, nightclub flyers—while Muertos keeps a firm grip on the core: the home altar and the cemetery night."

But some Mexicans remain firmly opposed to Halloween, fearing it will eventually supersede their nation's ancestral traditions. The two are spiritually very different, they say. Día de Muertos is when the dead are remembered and honoured; there is no fear involved. The spirits are welcomed back home and nurtured. It is a time of celebration and colour where death is 'dressed up' to remind us that it comes for us all, rich and poor. The practice pre-dates Samhain and Halloween. Samhain, the ancient precursor to Halloween, was a supernaturally intense time; there was an undertow of fear as people marked the end of their harvest and the beginning of winter. Its rituals were designed to scare away spirits, not welcome them and sacrifices were vital to this so that the Celts might prevail over the ensuing darkness. The two festivals feel very different to me.

I understand Mexican reservations about Halloween's ingress into their culture. You only have to look at Mattel's Día de Muertos Barbie to witness the literal manifestation of what happens when ancient cultural practices are commodified, losing much of their profound, rooted meaning in the process. The festival is itself a blend of Indigenous, colonial and post-colonial religious and cultural practices whose roots have been disputed by scholars. Some claim it originated with the Roman Catholic church before undergoing a post-hoc reframing as Indigenous cultural practices were embedded and reinterpreted. Others deny this, claiming it is only non-Latinos who confuse the two festivals and argue the biggest threat to Día de Muertos is foreign cultural appropriation, not arrogation by stealth in its native land.

Halloween is vulnerable to similar commercial and transcultural forces. Accusations of 'dumbing down' are common, as is criticism that its original meaning has been diluted in a sea of themed 'stuff'. Modern rituals, say critics, have precious little to do with Samhain and its successor, All Souls Day. One person even gravely informed me that "Trick or Treating arrived here because of ET". There's a grain of truth here: our diet of American media has had some influence, and the same holds for Mexico. In a weird inversion, the rise of Mexican-themed Halloween products on UK shelves can be attributed to the UK's misunderstanding of Día de Muertos as 'Mexican Halloween'. We have ghost-shaped tortillas and 'sugar skull-making kits'. Freshly baked pan de muertos are available online; their popularity extends beyond the Mexican diaspora. You can buy a 'spooktacular' Chipotle chicken roll, 'Exploding Chocolate Skulls' and skulls made from 'Mexican Chilli Chocolate'. Other cultures have been 'referenced' (my polite word for what is happening!): check out Halloween Fortune Cookies, Zombie Bao Buns ('with a Deliciously Ghastly Icky Sticky Sweet & Sour Filling'), Aldi Halloween Aaahmazing Bao Buns Sweet & Sour Veg Pumpkins, Hell-oumi fingers, and Lebkuchen Witch Biscuits. I have yet to find 'Screaming Samosas', 'Aloo Ghostbi', 'Manghost Lassi', 'Curry Ghost', or 'CallaWoo' as of yet, but give it time.

Online Halloween party food sections are a parade of crisps in the shape of ghosts, worms, bats, bat fangs, and vampires. The worms are pickled onion-flavoured, the bat fangs are cheesy. I can buy Freshly Dug Sweet Bags filled with bones, hearts and skulls, lollipops shaped like zombie fingers or haunted heads (the latter an accurate depiction of my disposition after two hours on Google), and a chocolate toad filled with 'fizzy bubbles'. There are Ginsters 'limited edition' Spicy Sausage Halloween Pasties, Scream Cookies 'n Cream by Soreen (makers of the austerely beautiful malt loaf, the queen of Plain Cakes), a 'Mummified Meatloaf', Jack 'O Lantern-shaped crumpets, and 'Ghouliflower' popcorn, boxes of Terrifying Toffee Rolls and Fiendish Fancies from Mr Kipling, bottles of pumpkin spice chocolate liqueur, pizzas shaped like eyes, and exploding chocolate truffles. I should say that most of these products lure us in with clever (or not-so) wordplay; the products are essentially the same ones available year-round.

I can dress a dog up as a spider or witch and buy it a pack of Halloween Toffee Apple Dog Chews, kit myself out in designer clothes from Liberty in the style of Harley Quinn or buy a J.W. Anderson frog clutch bag. Local nail bars are advertising spooky nail art. For toddlers, there are Jellycat toys in the shape of a toffee apple, skull-shaped plant pots (complete with fabric plant) and something named 'A Screaming Ball' which, to be honest, sounds like your average newborn baby. We can dress our beds in a duvet patterned with 'gothic moths' and wear skeleton pjs before turning off the Big Light, a giant resin pumpkin-shaped shade whose design has been ripped off from Yayoi Kusama. There's matching pumpkin patch-picking outfits for the inevitable Insta photos and a 'spider party' kit (although in my house the arachnids have been partying since late August), 'spooky' trunks for men (so unsexy my vagina sealed shut at the sight) and women's briefs patterned with skeletons riding on stars. I quite like a doorbell in the shape of an enucleated eye. I do not like a set of bloodied stick-on handprints for windows. There's even a Friday 13th 'Jason' wooden chopping board, but I draw the line at cushions emblazoned with the faces of notorious child killers (I mean, WTF?!) On a previous trip to New Orleans in the run-up to Halloween, I grabbed a handful of glow-in-the-dark condoms patterned with 'sexy ghosts'; I'd die laughing if a man approached me dressed in one of those. All that's missing is an emergency oral contraceptive Halloween movie tie-in. It could be called 'I Know What You Did Last Night.'

Bury St Edmunds, the town where I live, was the site of two internationally infamous witch trials, a history that surely ranks it as one of the best places to celebrate Halloween. Think again. Back in the days of Twitter, I asked why Bury St Edmunds hasn't commemorated (or exploited) its witchy history. There are (to my knowledge) no monuments marking the loss of innocent lives, which, seeing as so many were women, shouldn't surprise me, and a dearth of printed 'witch trial' tourist trails or commemorative markers outside significant locations. A historian replied in words to the effect of "God no, we'll end up like Salem, overrun with Halloween tourists and goths."

Having spent a fair bit of time in the US in the run-up to Halloween, I can think of worse things than being overrun by goths celebrating 'Goth Christmas' (they are a famously gentle, non-violent subculture), but underpinning his (albeit loftily expressed) objections are genuine concerns about the problems caused by tourism related to a particular event, something that the annual Whitby Goth Weekend has to contend with. Traffic chaos and crowded streets render the town almost unusable for locals. As the event's remit broadens, attracting members of other subcultures, similar accusations of 'cultural dilution' from old-school goths protesting the large presence of 'goth cosplayers' and steampunks have emerged. It's fascinating. Salem itself was accused of gentrifying itself out of its spooky history back in 2016, although this didn't deter tourists; more than 2.2 million people visited Salem in 2023. This season, some businesses in Salem have expressed concern about a decline in international tourism.

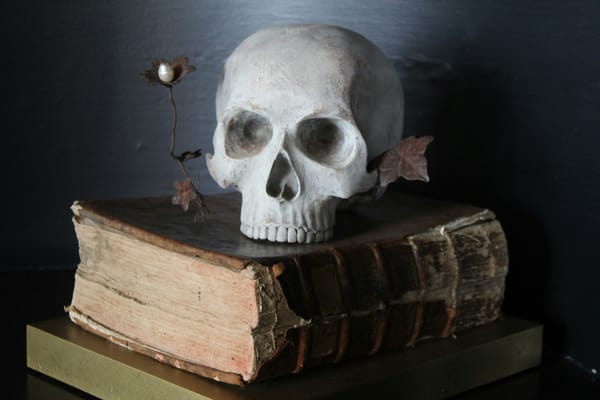

My town's involvement in the witchcraft trials is too important to be reduced to a small (albeit good) display in the town's museum. It is inextricably and directly related to Salem's own witch trials. The 1645 case judgment by Sir Matthew Hale from Bury St Edmunds' first trial was referenced in Salem and possibly used as a model for the increased persecution of people believed to be practising witchcraft in the American colony. Overseen by Matthew Hopkins, the self-titled 'Witch-finder General', 18 people from all over Suffolk were brought here, tried, convicted and executed on unconsecrated ground at Southgate Green on the town's perimeter. In 1682, the trial of Rose Cullender and Amy Duny was documented in A Tryal of Witches, At the Assizes Held at Bury St Edmunds for the County of Suffolk, written by an anonymous observer. The publisher also chose anonymity. The book was not published until 1716, a year which saw the last execution in England of a woman accused of witchcraft. (The 300-year-old book went on display at Moyses Hall Museum in January 2025.)

Bury St Edmunds is no different to anywhere else in not letting the truth get in the way of a good story, though. A local pub, The Nutshell (which also claims the title of 'smallest pub in England'), is said to have been built on the site of a building where the accused witches would be taken to await their execution. In preparation, nails and locks of hair would be clipped and stored inside brown glass jars kept in the basement. It was believed a witch would return to continue their nefarious activities if they died 'whole'. Yet I have yet to find confirmatory evidence of a holding place for witches on the site of the Nutshell, although a gaol was established around 1655 in a building on the corner of nearby Woolhall Street and Cornhill. All our local tourism sites repeat the story sans evidence. The town is underserved by this proliferation of factoids about our witchy history, halfheartedly promoted by organisations and businesses who should know better. It's a wasted opportunity.

This lack of civic record can't be because we're squeamish. A local museum has on display a book bound in the flayed and tanned skin of William Corder, the Polstead Red Barn murderer of Maria Marten. There's a memorial to the 57 Jewish townspeople massacred on Palm Sunday in 1190, where the annual Holocaust Day service takes place. Edmund, the King of East Anglia and the saint for whom the town and abbey gain their name, was murdered by the Vikings, 'death eagle'-style, before being beheaded. Edmund is well remembered: a statue of a wolf with the local rugby team's scarf around its neck sits on a roundabout; another roundabout is home to a rather gory statue of Edmund, pierced with arrows; and then there's the town's name. One local ghost, 'the Grey Lady', is promiscuous when it comes to her haunting grounds, being seen all over town by multiple people, and the mummified cat that hangs over the heads of customers at The Nutshell is reputed to be cursed, bringing bad luck to anyone who moves it. After it was touched too many times by tourists, the pub's owners had the cat entombed inside an acrylic box. Unfortunately, they weren't able to do this in situ, and the cat had to leave the building. Yesterday, I asked after the well-being of those involved. I'm glad to report they are all still alive and well.

In winter, the town centre of Bury St Edmunds is an austere sea of grey and brown. The Arc, our newest shopping precinct, is a particular culprit. Its buildings are grey, the paving is grey, and the skies above are frequently grey. Even the grey planters contain grey-leaved olive trees. I wish it weren't so. I wish we had a Halloween witchcraft trail and a monument to attract more life and colour to the town. Instead, in-store Halloween decorations serve their purpose as a brief, bright distraction from the grey. Inside one shop, a display of fat pumpkin mugs, furry and squashy squash-shaped cushions, table mats patterned with benign ghosts, and garlands of autumnal leaves and flowers made me smile. A rampant display of consumerism, you say? Yeah, I know. These goods will likely end up in a landfill or, at best, charity shops or on Vinted; I agree we don't actually need them and instead should wander the countryside gathering freshly-fallen leaves instead of buying fake ones, and eating the pumpkins we bought for display instead of cruelly discarding them (here's a useful guide to the most delicious varieties, and a book of recipes). But that display of cheap pumpkin mugs with gold lids shaped like a stalk cheered me up. I watched groups of teenagers wandering the store carrying baskets filled with Halloween decorations and costumes, and thought how lovely it was. These mass-produced pieces of impermanence felt earthily ancient; I began to imagine how I might incorporate a pumpkin mug into my life.

Halloween and Día de Muertos's sensory overload still feels atavistic. We continue to march to the beat of ancient drums even if we're dressed like Freddie Krueger. Local children will trick-or-treat, there'll be Halloween Drag Nights, and streaming platforms will be flooded with horror films. The pub playlist might include the Sisters of Mercy. They'll offer cocktails with suitably ghoulish names and witch-shaped stirrers. The Halloween haters will continue to grumble that all this is meaningless compared to the rather nebulous 'good old days', an established ritual in itself, rivalling that other old chestnut, 'Muslims have banned Easter eggs' (they haven't; if you believe they have, you're gullible, stupid, and racist). As tacky as they might seem, those bags of candy in the shape of body parts, plastic lanterns, and bat-shaped crisps are mass-produced symbols deeply rooted in the soil of our ancestral, collective pagan past. We continue to defy the coming darkness, and I am here for it.

Further reading:

“I should add, however, that, particularly on the occasion of Samhain, bonfires were lit with the express intention of scaring away the demonic forces of winter, and we know that, at Bealltainn in Scotland, offerings of baked custard were made within the last hundred and seventy years to the eponymous spirits of wild animals which were particularly prone to prey upon the flocks - the eagle, the crow, and the fox, among others. Indeed, at these seasons all supernatural beings were held in peculiar dread. It seems by no means improbable that these circumstances reveal conditions arising out of a later solar pagan worship in respect of which the cult of fairy was relatively greatly more ancient, and perhaps held to be somewhat inimical.”

― Lewis Spence, British Fairy Origins