Indigenous Australia: Suffolk Sound Radio Show Notes 15/10/25

Here are all the links from my Suffolk Sound radio slot on Wed 1 October. I was delighted to interview Carrie (Caroline) Fitton, an experienced travel journalist for The London Evening Standard, and contributor to other national newspapers and magazines. For the last 12 years, she has worked in conservation with the Wildlife Trust in Cambridgeshire, writing a monthly column in the Cambridge Independent that covers the wide variety of invaluable work undertaken by the Trust. Carrie has been visiting Australia for over 50 years, and came onto the show to discuss tangible changes that have taken place in the past decade regarding the visible accreditation and acknowledgement of Indigenous land ownership, culture and experience. It's been a long time coming in Western Australia (WA), she says.

We discussed terminology (Indigenous/First Nations/Aboriginal). This is a useful guide. Basically, ask how people like to be identified and described.

Carrie spent three months in Australia visiting family last year, where she encountered WAITOC (West Australia Indigenous Tourism Operators Council), a wide collective of 200+ Indigenous tours and experiences. Visitors can enjoy bushfood experiences, cultural tours, galleries, festivals, arts, crafts and food from Indigenous-owned businesses whose 45-65,000 years of knowledge is rooted in a fundamental and deep respect for the land. WAITOC's vision is to see the creation of a vibrant, authentic Aboriginal tourism industry as an integral component of Australia’s tourism industry and for Western Australia to become the premier destination in Australia for authentic Aboriginal experiences.

Carrie also recommends this website.

Closing the Gap - Indigenous tourism in Western Australia

We discussed how to be a responsible, mindful tourist and raise awareness of the cultural injustice done to Indigenous people. Supporting their businesses is an intrinsic part of this. Carrie told me that British visitors to Australia are less likely to spend time (and money) on Indigenous-run experiences than their mainland European neighbours. This is a shame.

Carrie visited Shark Bay and spent time with Darren 'Capes' Capewell, creator/owner of Wula Gura Nyinda (‘you come this way’, a traditional term for the sharing of stories) and a descendant of the Nhanda people. Based at the Francois Peron National Park and World Heritage site, Darren's tours explore the ancient cultural ties of the region’s Nhanda and Malgana People to the place they call ‘Gutharraguda’.

"Capes, as he's known, grew up in this place – he and his brothers rode horses around the area that's now a World Heritage site – it's their backyard," she says.

"It's immediately evident he has an innate inbuilt respect for the land – it's as if he knows every salt bush, every lizard, every bird, every thorny devil . . .The knowledge has been accumulated and passed on over thousands of years. He'll spot a dugong, shark or turtle in the Indian Ocean in seconds, name every plant we pass, pluck a wild bush yam from the ground (like beanshoots). It's a bewitchingly beautiful place with deep azures in the sea and sky, contrasting with copper and coral sand and rock – the strength of colours is almost unreal."

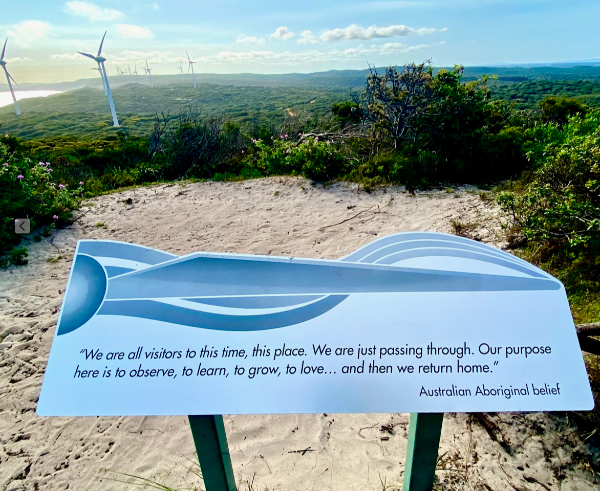

We listened to Carrie read two great quotes from Capes:

“It is becoming increasingly clear to us that our guests are aware of the human impact on Country (nature). They want to work with us to create an educational platform to change the way in which we interact with nature. They don't just want to travel to visit and see iconic places, but want to delve deeper and have a meaningful experience. They want to do their bit to make positive changes in society whereby people understand more about our relationship to nature and work to reduce our human footprints.”

“We have many take-home messages for our guests. One is to try to understand our emotional relationship to Mother Nature, and to be humble and grateful for that presence. We are a World Heritage Area - at Wula Gura Nyinda we provide an educational platform to do our bit to ensure that this is at the forefront of our business model. Our job is to look after Country (nature) and with so much pressure on our marine and terrestrial eco systems, we invite our guests to do the same. We believe that nature is our medicine.”

We didn't have time for this memory, but I'm including it here:

"Huddled halfway up the beach, an exhausted cormorant was hunched over, its head bowed, looking to the sand, back turned to the Indian Ocean and the vast skies above Shark Bay, the place where it had spent its freewheeling life," Carrie writes. “This is what they do when they know there's nothing left in the tank,” explained Capes. As we drove slowly by, his right hand made a circular gesture, almost as a blessing: “Fly free, brother, have a good life.” Devoid of maudlin sentiment this tender, respectful acknowledgement of a life passing seemed to encapsulate the Aboriginal/Indigenous ethos of acceptance, of being one with nature and the universe."

Carrie dislikes the 'bushtucker trials' of ITV's I'm A Celebrity show, believing they disrespect and trivialise true Indigenous bushfood cultural practices. Her dislike deepened after spending time with Dale Tillbrook, a Wadandi Bibbulman elder, to explore 'the real bush tucker'. (Info here.) It's definitely not a trial, Carrie said, going on to describe some of the ingredients she tried, and the meals made from them. Here's her accompanying notes:

- Wild bush food is delicious - there are a huge array of plants, herbs, seeds and nuts – many with both culinary and medicinal uses.

- Lemon myrtle – has the highest citral of any plant in the world – leaves are crushed to make tea – high in antioxidants, used in cakes, (there are also many different myrtles.)

- Saltbush – chew the leaves – the plant extracts salt from the soil. It's used in soups and stews, wrapped around fish to imbue flavour and you can deep-fry small branches for a crispy, salty and zesty snack. This would be a great way to prepare samphire.

- Geraldton wax (Geraldton is a coastal town midway along the WA coast – but the plant is widespread). This is a common, easy-to-grow plant with thin, spindly leaves (imagine a delicate rosemary). Flavour-wise, it's similar to aromatic lemongrass. Delicious used chopped on salads, to flavour curries, etc.

- Sandalwood/Quandong (Santalum acuminatum) –a type of sandalwood whose edible fruit is the quandong. The outer soft fruit is used to make quandong jam, used in tarts (Dale had made some) or chutneys, with a slightly sour flavour; imagine a peach crossed with aniseed. Also used as a hair conditioner, for treating bruises and skin conditions. The kernels can be crushed, grated or roasted, with an almond flavour - also used decoratively.

- Wattle – 1,000 species of wattle, 100 of which are edible – the seeds can be toasted and crushed to add texture as toppings, and to thicken and flavour soups and stews. It's high in protein, and the seeds can be ground into flour and mixed with other flours.

- Native limes – finger limes – red skin containing delicate pearls of citrus which can be squeezed out – rich in flavonoids; shaped like an index finger. Wild finger limes are genetically diverse, with fruit varying in size, shape and colour – from lemon yellow to bright pink, filled with hundreds of spherical ‘pearls’, each with a distinctive citrus flavour.

I mentioned Lara Lee, an Australian chef and food writer who has Indonesian heritage. A few years ago, Lara sent me a parcel of Australian herbs and spices, nearly all of which were new to me. The powdered wattleseed tasted quite cocoa-y so I used it in ice cream. (And I remember buying wattleseed from Sainsbury's of all places, but that was a long time ago!).

What comes singing through is the deepest respect for the land, for all natural life and that we are just custodians – living with the land, not on it. As Dale says: “We are all a part of all that there is - these rocks and plants are just as important as us – so looking after Country is of prime importance.”

Carrie noted visible changes: signage in Noongar first, English second; and the once-colonial museum of WA is now reimagined as Boola Bardip ("many stories"). The entire ground floor is dedicated to Aboriginal / Indigenous history and culture.

I was intrigued by Carrie's descriptions of sustainable abalone farming. She met Brad Adams, an abalone diver in Augusta who has developed a sustainable reef on which to grow and then harvest the green-lipped abalone. This 'reef-dwelling snail' (Brad's description) has a delicate flavour prized by chefs and cooks, particularly those from East and South East Asia. I haven't tried abalone, but it sounds not dissimilar to conch, which I have eaten in southern Florida. In the UK, super-fresh whelks are a pretty good alternative. This led us to discuss the concept of British 'Indigenous' food and how toxic this debate can become. Many of our traditional foods and culinary practices are ancestral and ancient, and some are also indigenous (or 'native'). A few are undervalued; the whelk is one of them. In the British Isles, we harvest the edible native European and Northern Atlantic species commonly called the "dog whelk"(Nucella lapillus); the banks that lie forty miles off the coast of Lowestoft in Suffolk are a prime whelking spot. Fishermen use large ‘inkwell-style’ whelk pots made from thick Stockholm-tarred rope fixed to a heavy metal base plate. Most of the UK whelk catch is exported to Spain, France, East and South-East Asia, where it is prized, its meat a substitute for the rare and expensive, warmer-water conch species. Whelks are in season until February, and in the UK, it's traditional to eat them with a sprinkling of vinegar, salt and pepper at the seaside. I didn't have time to describe what to do with them, but here are my notes:

Sashimi. Or in spring rolls.

Cooked French-style with garlic butter and parsley or in bay, thyme and white wine-scented water to be eaten cold with aioli.

Fritters in the manner of conch.

I've heard you can pickle them. (In the American South, they pickle shrimp, and it is delicious.)

Served with roti, cooked with green chilli, Thai basil, lemongrass, and fish sauce.

A tomato chowder similar to the version made with conch and served to me near Estero Beach on Florida’s Gulf Coast. I like the sound of this Bahamian Conch Salad which would suit whelks, and Nina Compton's Conch in Sauce Souskaye. Her New Orleans restaurant is a favourite of mine.

Korean Golbaengi-muchim, the sweet, sour, and spicy whelk salad served after you’ve drunk a lot of alcohol. (Contains hot pepper flakes, sesame, Korean pear, onions, garlic, ginger and wheat noodles. Here's a video showing you how to make it.

Still on the subject of all things marine, Carrie described 'Ocean Floor Cellaring' where 300 litre vats of Margaret River Region wine are submerged to undergo their secondary fermentation process. "The usual manual stirring of residual yeast will be handled by the ocean, its currents, tantrums and whims, effectively keeping the lees in constant suspension throughout the process," says Rare Foods Australia. Carrie gave a lovely description of the coralline-patterned bottles.

Returning to the subject of Indigenous/Native versus Ancient foodways, I discussed East Anglian salt production, a practice that evolved in tandem with humankind. We cannot live without salt. The East Anglian coastline and tidal marshes were critical for salt production, particularly in the Roman period. Archaeological excavations have revealed the remains of vitreous flat-bottomed vessels used to evaporate brackish water, leaving behind its salt. The fragments left behind, together with the remains of salterns (large pits scorched red from years of burning), gave us the term 'Red Hill' (a small mound with a reddish colour found in the coastal and tidal river areas of East Anglia). Over 300 Red Hills have been identified along the Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk coasts.

Suffolk Sea Salt:

Together with the Suffolk Sea Salt Company, Intra Laboratories produces a natural sea salt from the estuary waters of the Rivers Orwell and Stour. It is filtered to remove impurities and poured onto plates to dry in a low-intervention process.

Southwold Museum has a section on its website devoted to the history of saltmaking in Suffolk.

During the course of my research, I was dismayed by the number of features on the subject of Indigenous food and cooking that solely referenced (and quoted) non-Indigenous chefs, restaurateurs and food writers. So I've compiled a short list of Indigenous Australian chefs, cooks, writers and cookbooks.

Zach Green runs pop-ups across Aus. He told The Guardian: “At 12, I discovered a family secret: my grandmother was Aboriginal, part of the stolen generation. I took pride in the revelation, telling my new high school friends that I was a Gunditjmara man. The racial abuse I received in response silenced me for the next five years.

“Greater knowledge of our unique produce must be coupled with an understanding of the stories behind the food, because these stories are also a way for us to understand the pressures that native food production in Australia faces. It’s not as simple as encouraging people to eat more kangaroo, saltbush or witchetty grub.”

Nornie Bero is from the Meriam People of Mer Island in the Torres Strait and is the Executive Chef, CEO and Owner of Mabu Mabu. Bero has been a professional chef for more than twenty-five years.

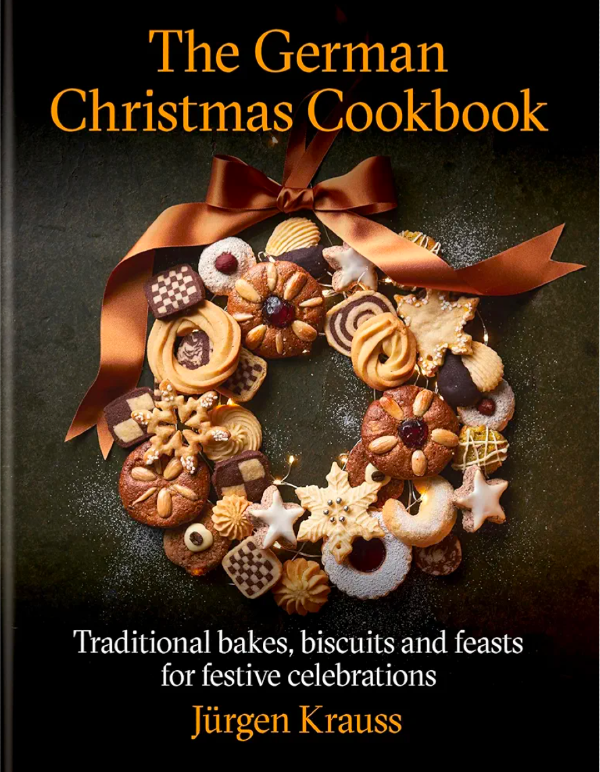

First Nations Food Companion by Damien Coulthard and Rebecca Sullivan. Indigenous recipes are in historical colonial documents and early cookbooks (fern syrup and native currant jam feature in an 1843 recipe collection printed in Australia), but are unattributed. Damien is Indigenous and, together with Sullivan, seeks to redress this. They have also coauthored Warndu Mai (Good Food): Introducing Native Australian Ingredients to Your Kitchen.

The Native Harvest Kitchen cookbook is free to download from the University of Melbourne. “While native ingredients might currently be considered high-end and trendy, they should be integrated into everyday meals alongside staples like strawberries, spinach, and wheat," say its authors.

Aunty Beryl: A respected figure in Indigenous nutrition and bush tucker.

Lara Lee’s debut cookbook, Coconut & Sambal, traces Lara’s Indonesian heritage, from discovering her Timor-native grandmother’s recipes to island-hopping across the Indonesian Archipelago. She grew up in Sydney.

Bruce Pascoe on Indigenous rights and responsibilities to the land. I have ordered his book, Dark Emu.

Kukumbat gudwan daga: really cooking good food created by women from the women’s centres of Manyallaluk. More background on this cookbook, here.

How can your restaurant or food business support Indigenous foodways? asks this piece.