Cosplaying an old mountain woman

Out for a walk. Underfoot, a bosky mulch of fallen leaves. The air is suffused with the scent of wood smoke; the last few nights have been cold enough for blankets over laps and fires to be lit (and in our case, the heating has been put on). It's quite a shock.

Ubiquitous autumnal prose aside, I'm not mad about this time of year. School was miserable most of the time (bullied at home, bullied at school), so September, the start of a new academic year, did not fill me with anticipation. No amount of woolly tights in bright colours, new pencil cases, and Insta shots of Caran D'Ache pencils in shades of feuille-morte will make me love autumn. ("To make a countryman understand what feuille-morte colour signifies, it may suffice to tell him, it is the colour of withered leaves in autumn" — John Locke.) Jane Eyre's displeasure at the "silent trees, the falling fir-cones, the congealed relics of autumn, russet leaves, swept by past winds in heaps, and now stiffened together," spoke more of the discomfort she felt after standing up to her benefactor, but it certainly speaks to my sagging spirits at the onset of the season of mists and increasing fruitlessness.

Yet autumnal atavism is hard to avoid. Memories of school harvest festivals in Mexico and England, the avid consumption of books for children* steeped in rural life, and grandparents who were experts in coping with food gluts retain their emotional gravitational pull. Driving along country roads (passenger seat!), I am hawklike in my search for wild fruit half-hidden in the scribbly hedgerows; it's a matter of training one's eye to 'look through' the branches as one does when birdwatching until, suddenly, hundreds of wild plums and bullace, sloes, rosehips, and apples emerge from the shadows. I assume the plethora of apple trees along our local 'A' roads has grown from thousands of cores carelessly discarded from car windows, but not every wild-grown tree produces fruit good enough to eat; we have favourites, a result of trial and error. Some trees hover precariously close to main roads (including a Pitmaston Pineapple), and others require less commitment to pick.

On Sunday, we visited our regular trees, returning home with carrier bags filled with fruit (sorry, I am not a wafty wicker trug woman, no matter how much I'd like to be), and I've been processing them (horrible term) ever since. Three heavy pans of apple butter blip away on the stove as I write this. There are many, MANY newsletter posts waxing lyrical about the smell of apples if that's your thing, so I won't bore you with overwritten paragraphs about the Bleeding Obvious, other than tell you about Bunny Mellon, the famous American socialite, patron of the arts and designer of Jackie Kennedy's rose garden who was said to keep a pan of apples cooking on her stove at all times to suffuse her country estate with their homely, nostalgic comfort. Her fruit was grown on espaliered and cordoned trees at Oak Spring Gardens, now immortalised in a design by wallpaper company De Gournay who describe it as a trompe l’œil of "mouldy apples, tangles of cobwebs, and fallen pears left to rot on the grass speaking to Mrs Mellon’s dichotomous approach to garden design that marries a natural insouciance with meticulous control."

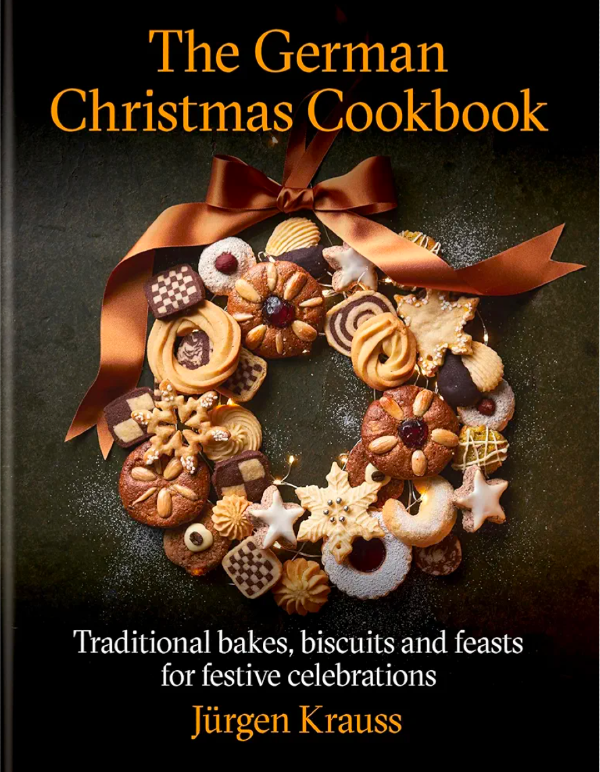

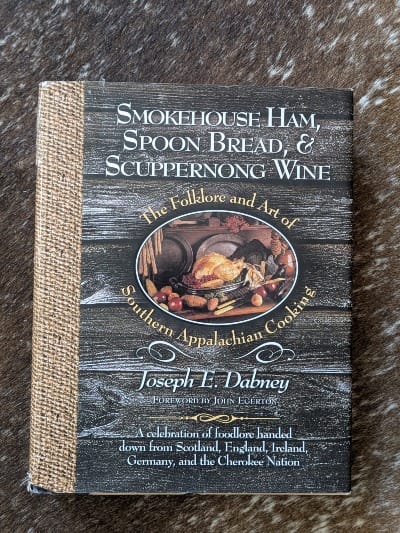

I do not have a country estate and relinquished our allotment last year after repeated vandalism, theft and muntjac deer attacks. I haven't dared return to see if the new owners have kept my pair of fine russet apple trees (Egremont, Hereford) grown on dwarfing rootstocks. What I do have is a well-stocked bookshelf packed with cookbooks by Appalachian and Indigenous authors to whom I return (atavism again!) each autumn to leaf through chapters on preserving the fruits of one's labours for the coming winter. East Anglia, where I live, is relatively flat, although my house lies on the crest of the highest point in our town, but that's never stopped me from cosplaying an old mountain woman when it's time to process two of the carrier bags filled with apples into apple butter. My favourite recipe is in Joseph E. Daubney's Smokehouse Ham, Spoon Bread, & Scuppernong Wine in a chapter titled 'Jams, Preserves, and Oh, Glorious Apple Butter' (which should be a hymn). I've adapted it because the original calls for a 12-gallon ('copper if possible') cooking pot, 4-5 bushels of Stayman Winesap apples "picked within hollerin' distance of Hendersonville, N.C", 2 gallons of apple cider (juice, basically), 20 pounds of sugar and a quart of sorghum syrup. It also calls for an open fire, which I also do not have. Quantities like this make sense in situ; Daubney tells us how the recipe's creator, one Jim Hall of Asheville, turned apple butter-making into a communal party where guests would spend a day and night, watching and stirring giant pots after paring and slicing thousands of apples. Eventually, the amalgamated apple, cider and sugar mix would transform, becoming "as thick as hasty pudding" according to The Genesse Farmer of 1839.

Further reading/watching/listening:

*Alison Uttley, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Laurie Lee, James Herriott, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Susan Coolidge, Jennie D. Lindquist, Brian Jacques, and Mildred D. Taylor were some of my favourites.

Chími Nu'am: Native California Foodways for the Contemporary Kitchen by Sara Calvosa Olson has a beautiful recipe for Cajeta Apple Pie Crepes. Cajeta has its own story embedded in what happened when Spanish colonialism collided with local Indigenous culture, which Calvosa Olson writes about.

In Thomas Pecore Weso's Good Seeds: A Menominee Indian Food Memoir, we read about his grandmother's applesauce made with fruit picked in orchards in the grounds of a nearby Catholic church. Bears would frequent another of their picking sites on the Wolf River, using the caves that formed naturally as the waters swept along its curved banks. The bears preferred heavily fermented fruit, leaving the younger apples for humans to forage. "Drunken bears are not hard to identify. They stagger", he writes. "They roll on the ground with blissful smiles. They slur their growls." Cocaine Bears, they are not. Weso's grandmother would fill her shelves with apple butter, which appeared on the table almost every day, but her recipe isn't offered. Instead, we're given a recipe for Baked Beaver Feast where the (mainly) lusciously fatty tail meat is cut into pieces, rolled in cornmeal or flour and fried in butter until brown, then placed in a Dutch oven to braise in water with apples, carrots, onion and bay leaves. Thomas, who died in 2023, was a friend. We shared many a FB conversation about beaver meat, what it tasted like, and how to best prepare it.

An interesting piece about the crab apple and its use by First Nation People.

I enjoyed this review of the lovely The Ghost Orchard: The Hidden History of the Apple in North America by Helen Humphreys. Her book led me to Ann Jessop, an important figure in pomology: "There is nothing left of Ann in terms of anything she wrote, or said, or thought; what we have instead is something more intimate than any of that: her taste. She went to England and chose twenty apples, out of all the varieties that grew there in 1790, to bring back to America. She chose these apples—and that meant she tasted them, and she liked the taste of them above others. They weren’t chosen simply for their practical advantages—the long-keeping winter apples, for example—as there were other apples with these same characteristics. This was the heyday of apples, and there were thousands upon thousands of varieties. No, Ann Jessop chose the apples that she liked the taste of, and that she wanted to continue to taste when she set up her own orchards back home in North Carolina," she writes, adding:

"It is an intimate act, tasting an apple—having the flesh of the fruit in our mouths, the juice on our tongues. Ann Jessop bites into an apple in an English orchard in the hot summer of 1790, in the middle of her life, and I bite into the same kind of apple in 2016, in the middle of my life, and taste what she did. For the time it takes to eat the apple, I am where she was, and I know what she knows, and there is no separation between us."

Megan Larmer for Maluszine on how her unfortunate choice of word - 'master'- revealed the scale at which the racialisation of the American agricultural system has shaped the development of the cider industry. This led me to Black Orchard, whose project aims to collect data on black-owned orchards and farms across the United States.

Mark Powell's essay for the Oxford American about the apple orchards of South Carolina and the stories we construct as adults to make sense of our memories and their limitations when applied universally is so good.

I've reviewed Ronni Lundy's Victuals, one of the greatest writers on the subject of Appalachian food (and Southern culture in general). I use my apple butter to make her Appalachian Stack Cake.

Apple: Recipes from the Orchard by James Rich is very useful if you're cooking with British apple varieties.

Reference-wise, I recommend The Apple: A Delicious History by Sally Coulthard, The Apple Book by Rosie Sanders (beautiful watercolour illustrations), this guide to apples grown in the Welsh Marches, and Pete Brown's The Apple Orchard: The Story of Our Most English Fruit. I enjoyed pomologist Liz Copas and cidermaker Nick Poole's account of their decade-long quest to find and identify old varieties of cider apple trees around Dorset.

A while back, I wrote about my own quest to find a children's book whose evocative illustrations of apples are my pomological platonic ideal. I also wrote about the research underpinning my recipe for an Apple, Marjoram and Ricotta Cake with Burnt Honey Glaze.

Amy Bess Cook wrote an evocative piece for Imbibe Magazine about her return to Appalachian apple country. "I was born in Mount Airy, the inspiration for Mayberry on the antiquated, aw-shucks Andy Griffith Show", she writes. "If this sounds like a joke, it’s not—it’s my motherland." I own a copy of Aunt Bee's Mayberry Cookbook. Eight recipes use apples, including Andy's Red Hot Apple Sauce, which, they suggest, you serve at a 'Southern Pork Dinner'. If you don't know what Red Hots are, here's some info. Andy is referring to the candy, not a style of hot dog.

I enjoyed The Great British Food Podcast's episode with Joanna Crosby on the history of apples and orchards in England. And here's a CBC podcast episode with Simon Thibault interviewed by Portia Clarke. Simon is hugely knowledgeable about fruit and a super-intelligent and engaging writer. Here, he talks about the Belliveau apple, a nearly extinct Acadian variety that had once been grown and loved by his ancestors.

Canadian Geographic recently published a piece by Karen Pinchin about the Belliveau, which features Simon. "For Thibault’s ancestors, he knew, apples were both pleasure and subsistence: a reliable annual crop offering a backstop against starvation in lean years. But this apple — laced with cultural folklore, culinary heritage and a tangible link to his genetic lineage — represented something more."

This British Pathé footage from 1927 of the wassailing of cider apple trees is a treasure.

On the subject of autumn and the impending winter (shudders): "I'll learn to love the fallow ways", sings Judy Collins. The lyrics are beautiful, even if the genre or melody isn't for you. (It isn't for me.)

I'd love you to share this post!

(Some links go to my Bookshop.Org page. I earn a small commission should you buy from them.)