A timeless book on the history of British puddings

I'm updating and reposting some early book reviews originally published on my old Miller's Tale WordPress site. Although I love reading new cookbooks and frequently review them, particularly if they are written by authors traditionally underrepresented in Western publishing lists or cover interesting and unusual topics, my goal has always been to highlight excellent food writing, regardless of date of publication. Today's choice is a modern classic.

I revisited Pride & Pudding The History of British Puddings by Regula Ysewijn after receiving a press release from British Heritage (EH) in August. It claimed 'only' 2% of British households now make a daily homemade pudding, and 62% rarely or never make them at all. Obviously, this is the fault of women (when isn't it?!?) who, desperate to enter the 'seventies workforce', have been starving their families of good, home-cooked puddings ever since. In its haste to inform us about two new EH-branded pudding-inspired ice creams and a baking book launched off the back of this 'research', EH declines to ask why British men failed to take up the homebaked pudding mantle or interrogate why puddings remained popular during the rationing years of 2WW and its aftermath, when many women headed up their households in the absence of their menfolk whilst working outside the home in wartime jobs*. They were busy! Nor is there any attention paid to the changing nature of employment; these days, it is simply less physical.

“Sweet puddings are closely intertwined with British history..... and it would be a huge shame for them to die out", Dr Andrew Hann, a senior curator of history at EH, said at the time, and God knows this chimed with me. It would be a shame. I've been stewing ever since, not wanting to get sucked into what was a rather annoying PR launch, but maybe my review of this incredible book will inspire you to experiment in the kitchen, rather than buying 'pudding-inspired' ice cream.

Pride & Pudding, Style & Substance.

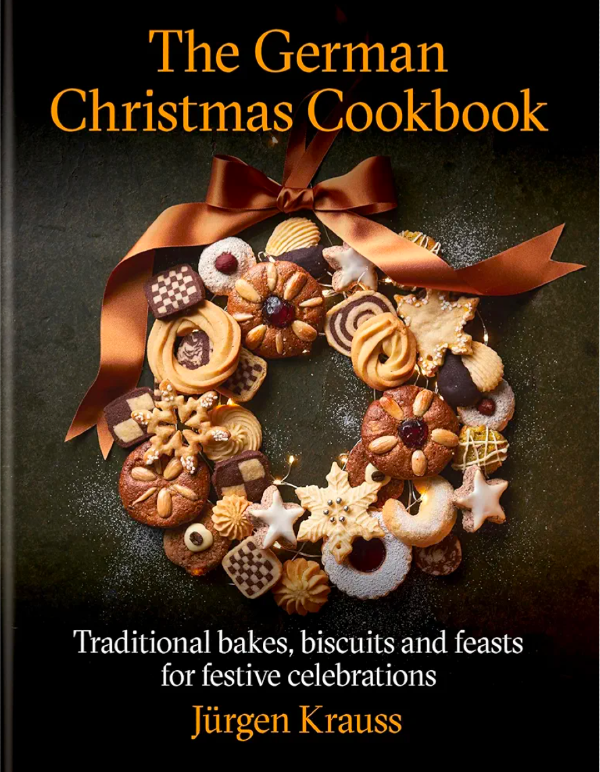

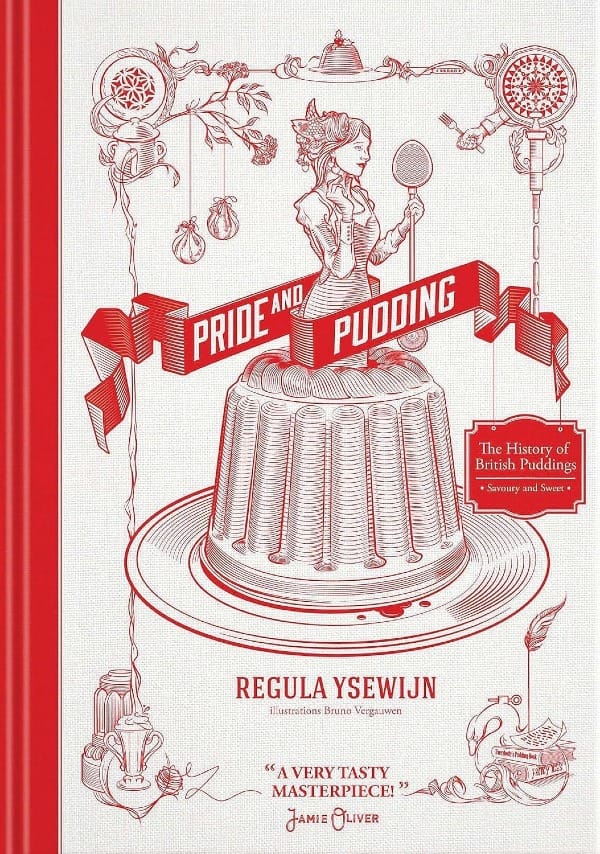

Some might say that pride and pudding are two things my life has a surfeit of, but I would argue that in the case of the latter, there is no such thing as too much of a good thing. And if I sound a little proud of that, then so be it. Enter Pride and Pudding: The History of British Puddings Savoury and Sweet by Regula Ysewijn, where the author’s in-depth exploration of historical cooking texts has led to a splendid and faithful recreation of over eighty puddings, both sweet and savoury. "Every book I write is about preserving a heritage, because in the present day, far too much importance is given to new and exciting things while the past holds a treasure of beauty that is often forgotten," she says on her website. By referencing each pudding’s original recipe against an updated version, Regula provides a contextual revival, helping us understand how and why recipes change over time.

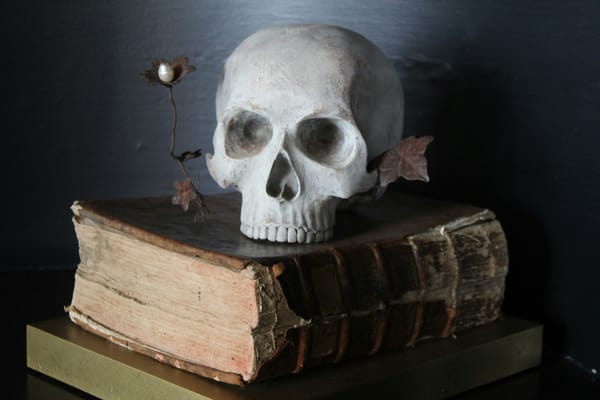

Regula's fascination with British food began in childhood. A self-acknowledged Anglophile, her rigorous academic and social research is coupled with an astonishingly beautiful way with words in English, her second language. (Regula is Belgian.) She attended art school in Antwerp, where she trained as a graphic designer and photographer; it is no surprise that Pride & Pudding's art direction is as meticulous as its academic research. Illustrated by her talented husband, Bruno Vergauwen, the book's Old Masterly feel is a clever compliment to the contemporary twist Regula affords her pudding recipes.

Why British food, you might ask. "British food has evolved much more than French or Italian food," she contends. "First by the different invaders of the island who each brought their own culture with them; then by the religious consequences of the Protestant Reformation, which forbade the richly spiced cuisines of medieval times," she adds, before exploring how The Enclosure Act and Industrial Revolution, wartime rationing, feminism, the rise of supermarkets and convenience foods, international travel and immigration, and our modern-day plethora of food media influenced British food and cooking.

The word ‘pudding’ sounds English to our modern ears despite a richly-textured etymological origin ranging from the West Germanic stem pud (to swell), a cognate of the Old English puduc (a wen), and the old French boudin (sausage), from the Latin botellus (sausage). Regula explores this in her introduction. In the modern sense, by 1670, the word ‘pudding’ had emerged as an extension of the method of cooking foods by boiling or steaming them in a bag or sack. As Regula points out in her foreword, in the eighteenth century, when English food was developing its identity once more, pudding was central to the process and represented a solid challenge to the tyranny of French food, the established shorthand for all that was refined at table.

Pudding has moved on from the stuffed vegetable recipe outlined in a Book of Cookrye in 1584 and the medieval technique of preparing fish, game birds and other beasts with a large pudding stuffed inside their belly although it took a Frenchman called Francois Maximilian Misson to declare “Blessed be he that invented pudding for it is a manna that hits the palates of all sorts of people…ah what an excellent thing is an English pudding.” Regula takes his lyrical tribute and runs with it, having amassed five years of blogging experience on the subject before writing her book.

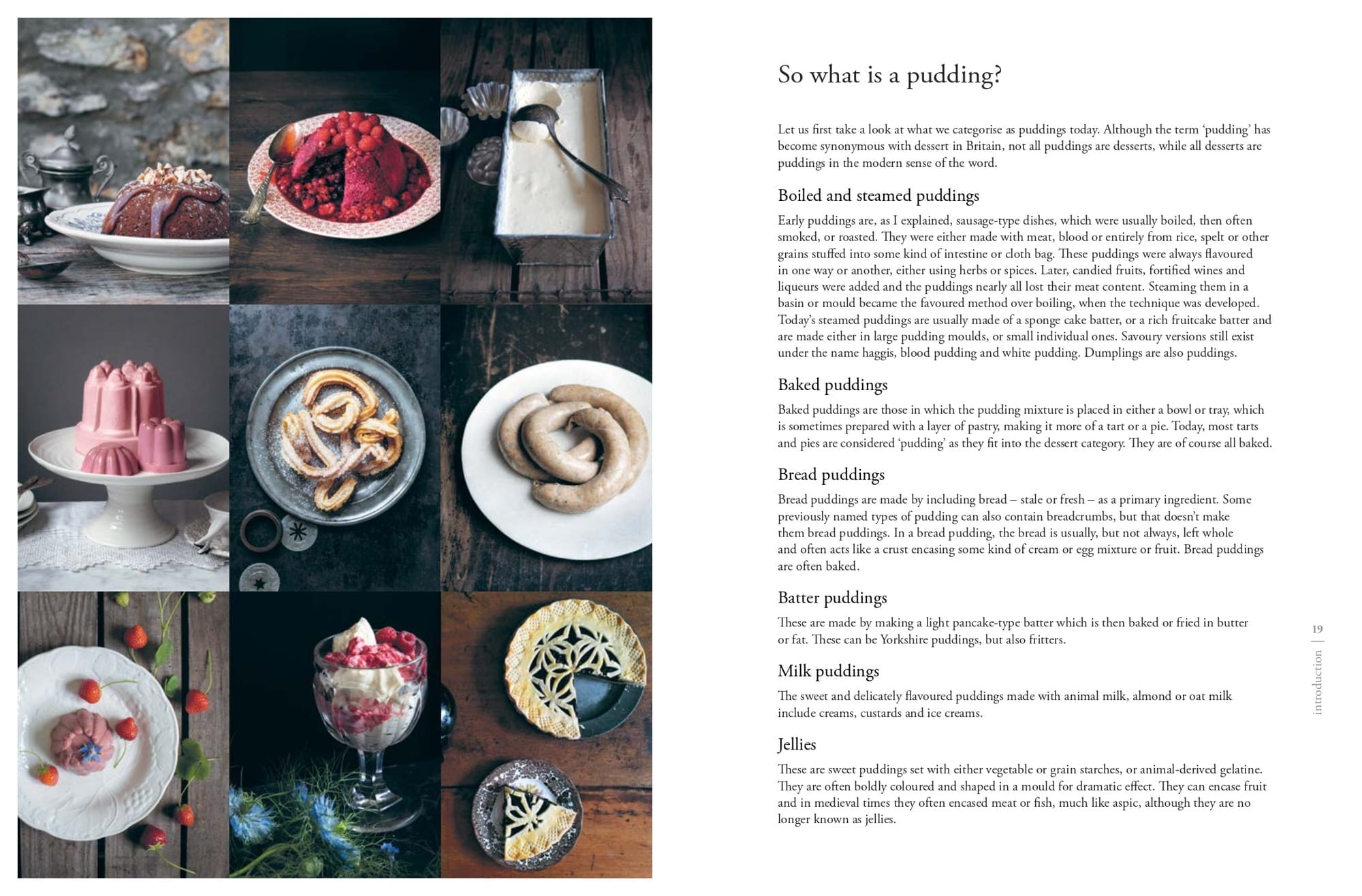

Pride and Pudding begins with a handy guide to the different types of pudding (bread, baked, milk, boiled etc) then launches into a historical account of puddings through the ages, from their first mention in Homer’s The Odyssey where black pudding was prepared for Penelope’s suitors to feast upon as they competed for her hand, through to the Romans, Vikings, Normans and onto the court cooking that was documented in the years following the Hundred Years War when plague, taxes and harvest failures led to widespread famine. Moving on to the Medieval period, Regula covers the foods eaten by the wealthy elite. A jelly made in the shape of a devil. A castle and a priest surrounded by a moat of custard. The first record of a pudding cooked inside cloth instead of animal intestines. The Reformation brought culinary change; elaborate Catholic-associated feasts were replaced by ‘proper, honest cooking’ (something familiar to those of us interested in aesthetic trends in food). The introduction of refined white sugar during the reign of Elizabeth I led to a sea-change in its use. Sugar was transformed into highly decorative sweetmeats for wealthy tables; patissières must have cursed as they nursed burns from sputtering hot pans of sugar. She lost her teeth.

Moving onto the seventeenth century, Regula tells us that French food regained dominance in Britain. Despite the prominence of this male chef-dominated cuisine, more cookbooks were written by British women than ever before, kicking off with Hannah Woolley’s book, The Queen-Like Closet, published in 1670. Traditional white and black puddings continued to be popular, and new puddings began to emerge (i.e. Woolley's Sussex Pond Pudding in 1672). The first published recipe in English for Snake Fritters was in 1660 in Robert May’s The Accomplisht Cook. These churros-like fritters made by pressing sugared dough flavoured with saffron through a buttersquirt into hot clarified butter with a (likely Moorish) heritage appeared all over southern Europe at the same time. The first printed recipe for a Quaking Pudding was published. She notes the first recorded mention of the Christmas Pudding in Colonel Norwood’s diary record from 1645. As we move into the eighteenth to nineteenth-century and Georgian and Victorian cooking, the focus remains on spectacle, with innovation in glassware permitting delicate milk puddings, syllabubs, and jellies to be displayed beautifully: If you thought Heston Blumenthal popularised food made to resemble something else, you’d be wrong; the Georgians delighted in creating flummeries that resembled bacon and eggs.

We read of Parson Woodforde’s plum puddings, pease puddings and a pike with a pudding in its belly, whilst Hannah Glasse makes the first print mention of the iconic Yorkshire Pud in her 1747 cookbook, The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy. The Georgian table was pudding heaven, and the Victorian street-traders made them available to the lower classes, selling plum duff and meat puds from steaming-hot baskets. Bookshops sold cookbooks entirely devoted to the pudding alongside Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery for Private Families, firmly locating the Angel of the Home back inside her kitchen unless she could afford staff.

So…what about the pudding recipes? They are categorised into six sections: boiled and steamed; baked and batter puddings; bread puddings; jellies; milk puddings; and ices. There's a section for master recipes, including clotted cream and custard-based sauces, various pastries, biscuits and flavoured vinegars. Regula incorporates notes at the base of some of the pages, annotated with a sweet illustration of a pudding spoon. For example, her Tort de Moy made with bone marrow, double cream, candied peel, and rosewater suggests you add almonds to the infusion used to flavour the custard, and her Devonshire White Pot can be cooked using a Dutch oven over a fire with its lid covered in hot coals instead of being placed inside an oven.

I’m particularly intrigued by a recipe for Devonian White Pot after reading about Newmarket Pudding, a local bread and butter pudding recipe. White Pot consists of buttery layers of bread, set with custard and layered with sweet, plump dried fruits. Unlike our modern-day version, where slices of bread are sogged in a mixture of sweetened cream, the White Pot is sogged with cooked custard made from egg yolks, cream and sugar. Interestingly, Newmarket pudding is the same pudding given a local name for no specific historical reason other than someone's desire for a rebrand. The better historical question to ask is not who ‘invented’ Newmarket Pudding but why someone might seek to rename an existing recipe? (Regula offers her insights towards the end of this Telegraph piece about British regional puddings.)

Photographic illustrations accompany recipes for Haggis and Black Pudding. Should you lack sausage casings, Regula shows you how to bake Black Pudding in a tray. A White Pudding is baked with saffron, pinhead oats, egg yolks, dates, and currants, and served in a single burnished coil with honey, golden or maple syrup. A delicate Castle Pudding is similar to a pound cake in its ingredient proportions, lightly spiked with citrus from curd, juice or thinly sliced orange rounds. Both the Sambocade, a cheese curd tart flavoured with elderflowers, and a flowerpot-shaped custard tart (Daryol) are made from hot-water pastry and decidedly rustic in appearance, a contrast to their delicate flavourings. I made the Prune Tart and it turned out beautifully, even though I longed to try the prunes mentioned by Gervaise Markham in The English Housewife. who wrote: “Take of the fairest damask prunes you can get, and put them in a clean pipkin with fair water, sugar, unbruised cinnamon, and a branch or two of rosemary; and if you have bread to bake, stew them in the oven with your bread…"

I was amused by a recipe for Jersey Wonders, little twists of dough browned in lard resembling female labia. (I may or may not be selling these to you, based upon that description!) I've bookmarked her Ypocras Jellies, the name for mulled wine in the Middle Ages, although, as she says, mulled wine has been around since Roman times. Mentioned by Chaucer in The Merchant's Tale, they're flavoured with spices ‘bruised’ by a pestle and mortar and richly festive, perfect for autumn and winter feasts when their cardamom, bay, nutmeg, clementine and sloe gin flavours naturally—and seasonally—shine. In the same section (jellies, milk puddings, ices) you will find all the indulgent flummeries, syllabubs, trifles, possets and bombes you could ever need. Perfect party food.

Technical stuff:

The extensive notes at the start of the book consider modern tastes and preferences: "Some dishes take a little getting used to because we have forgotten how some things taste", she writes. We are used to sweeter puddings now. Regula defines the term 'pudding', then traces its history, discusses the evolution of cooking techniques and ingredients (e.g. eggs used to be smaller) and how this influenced her recipe development. Weights are in metric and imperial. There is a comprehensive ingredients section and two lovely pages of writing on pudding and jelly moulds. We read about the challenges she faced in interpreting historical texts and her decision-making process. Pride & Pudding's bibliography and reference section is an extensive seven-page journey through gastronomic genealogy. I wish more cookbooks did this, even if it invariably results in my spending some eleventy billion pounds on yet more books and journal memberships.

Pride and Pudding: The History of British Puddings is published by Murdoch Books in Britain, Australia and New Zealand. Pride and Pudding was deservedly selected as one of the best ‘Books of 2016’ by Sheila Dillon of the BBC Food Programme, Delicious Magazine, the Irish Times and the Guardian. It was also shortlisted for the prestigious Andre Simon Award and the Fortnum & Mason Award and won the Gourmand World Cookbook Award for the UK, in the Food Heritage category. It’s a wonderfully useful and timeless book.

Regula has written and published several more baking books (Oats in the North, Wheat from the South: The history of British Baking and Dark Rye and Honey Cake: Festival baking from the heart of the Low Countries are just two of them), has won a James Beard Award and is a judge on the Belgian version of GBBO.

More reading:

Regula writes about pudding for The Guardian.

Regula's website.

*Here's an interesting Lithub piece by Jennifer Ryan on researching her novel The Kitchen Front, where she talks about her grandmother's experiences of cooking for her family during the 2WW: "Cooking was so central to women’s lives that when food rationing and shortages began in 1940, a revolution of sorts changed the very foundation of the way women found and prepared food. At the same time, women were becoming more independent, earning their own money, and finding more agency with the men away. Cooking and food were in the mix of the many ways women took control."